The introduction of new education, professional and ethical standards has been painful for many advisers. The process has been protracted, disruptive and costly. But even if the implementation has been difficult, there is a general view that new standards were necessary to help bolster the image of the profession and the standing of its practitioners.

But what if the time, money and energy committed by financial advisers, the disruption to their businesses and the stress created by additional study and sitting exams turns out to be for nothing? What if the public takes a look at the work the industry has done to date, and the work it will do in the next five years, and delivers a collective shrug of the shoulders?

In late 2016, when legislation was introduced mandating the new standards, the then-Minister for Revenue and Financial Services, Kelly O’Dwyer, said its objective was to enhance public confidence and trust in advice, and to have the industry operate at standards befitting a true profession. The intention was to emboldened more people to seek advice.

If the standards fail to meet consumer expectations or fail to increase trust and confidence in financial advice, or if they don’t persuade more people to seek advice, then they may be deemed to have failed. The good news is that CoreData research suggests strongly that the standards are well on-track to meeting their objectives, and that there is strong public support for both the substance and the intention of the standards.

Just not professionals – yet

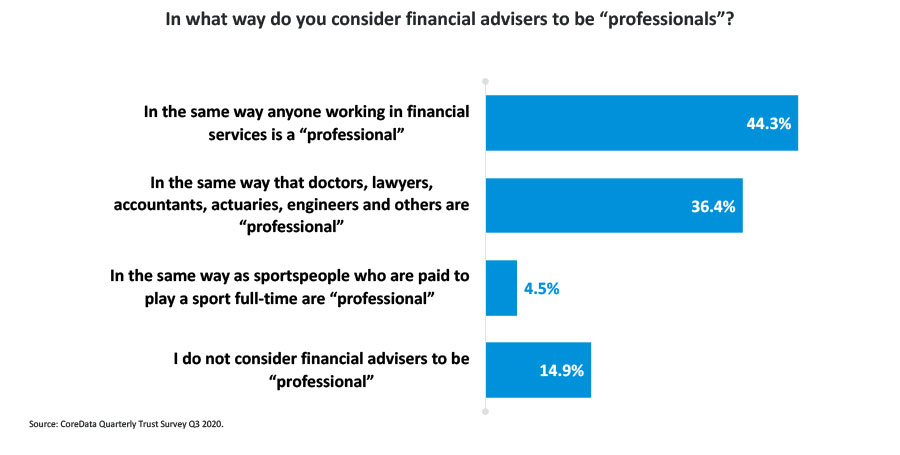

At the moment, just shy of two-thirds of Australians do not believe financial advisers are professionals in the same way they think of doctors, lawyers, accountants, actuaries, engineers and others as professionals. This includes 14.9 per cent of people who do not think advisers are professional at all, and 4.5 per cent who think of advisers as professional only in the same way individuals who are paid to play sport full-time are “professional”.

Even so, most people (86.6 per cent) expect advisers to be held to the same standards as those other recognised professions. More than seven in 10 (71.9 per cent) consumers believe an existing adviser should have a university or equivalent, or higher, qualification, and the greatest expectation (36.4 per cent) is that the degree should be financial planning related. Only one-third (33.2 per cent) believe the degree qualification should be financial planning-specific. There is strong consumer support (75.7 per cent) for existing advisers to meet the 2026 deadline to obtain that qualification.

For new advisers the story is slightly different. Fewer (67.8 per cent) consumers expect new entrants to the profession to be at least degree-qualified to get in, but more consumers (35.4 per cent) expect that a newcomer should hold a specialist financial planning degree. There is very strong support (92.9 per cent) for the Professional Year required of new entrants to the profession.

Talk it up

There is considerable scope for advisers to talk up their qualifications as they improve. Right now, about half of consumers currently don’t know if their adviser holds a degree or equivalent, or higher, qualification. Perhaps that’s because advisers who don’t hold one are reluctant to raise the issue in case clients conclude their adviser is somehow underqualified.

However, a significant proportion (45.9 per cent) of clients know their adviser does hold such a qualification, and it may be because these advisers explicitly address the issue as part of establishing their credentials. Among those consumers who do know their adviser’s qualifications, the largest group (33.1 per cent) says their adviser has a financial planning-related qualification, with just over a quarter (27.1 per cent) saying it’s a financial planning-specific qualification.

Industry-based qualifications, such as the Certified Financial Planner (CFP) or Fellow Chartered Financial Planner (FChFP) designation, carry some weight in consumers’ minds, with two thirds (68.9 per cent) believing they are an acceptable alternative to a formal academic qualification. But less than a third (31.0 per cent) of consumers think an adviser’s experience alone is an appropriate substitute for a formal qualification.

A tough examination

There is very strong (94.0 per cent) consumer support for the idea of advisers being required to pass an exam to test competency in certain areas, and the areas the current exam covers are strongly supported (89.5 per cent). The 2022 exam deadline is widely (81.5 per cent) considered reasonable.

While fully half (50.9 per cent) of all consumers do not know if their adviser has passed the exam, almost the same proportion (49.1 per cent) know their adviser has passed. FASEA chief executive Stephen Glenfield recently encouraged the industry to make more of the good news story that 10,000 advisers have passed the exam, and given the public’s support for the both the existence and substance of this test, he has a good point. But it looks like they already have been. Around half of all consumers (49.1 per cent) already know their adviser has passed.

The most common (48.1 per cent) exam pass-rate expectation is more than 90 per cent; this is only slightly higher than the actual pass rate of 86 per cent reported by FASEA to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics in June.

A significant majority (90.3 per cent) of consumers believe advisers should undertake continuing professional development to keep their knowledge up to date. Around 12.9 per cent think 31 to 40 hours is appropriate, in line with advisers’ actual requirement as set by FASEA. Almost one in five (18.7 per cent) think it should be more, although four in 10 (40.2 per cent) think it’s OK for it to be less.

But the acid test for all of the time, work and money that advisers are putting into meeting the new standards is whether it improves confidence in the industry, and whether more people consequently decide to investigate the benefits of financial advice for themselves.

And on this count there’s good news. Almost seven in 10 (68.7 per cent) consumers say that as a result of the FASEA standards – a bachelor’s degree or equivalent, or higher, qualification; an exam to test advisers’ competency in certain areas; and a minimum level of ongoing professional development – they are somewhat more or much more likely to seek advice.