Here’s the problem with creating trust benchmarks for financial planning: It’s tricky. It’s tricky because trust is a complex psychological construct; it’s tricky because trust is uniquely personal; and it’s tricky because financial advice is an experience, not a good.

We have to pause here for a second and think about this. Building trust in goods – things like cars or computers – is a function of reliability and ease of use, both of which are a function of price, which is why the price of goods can become a proxy for quality and trust.

For experiences, price and trust aren’t correlated, and price is a weak indicator of trustworthiness.

There have been about 200 years of psychological and biological research on trust, and the most frequently cited, and possibly most reliable framework for understanding trust in a service, doesn’t include price or usability. Rather, it includes four key ingredients: competence, benevolence, authenticity and predictability.

The list is the work of American Scholar D Harrison McKnight, who didn’t start out as a social researcher but as a computer analyst, and apparently blundered into the idea of the framework while setting up systems to run airlines – an industry where trust is very important.

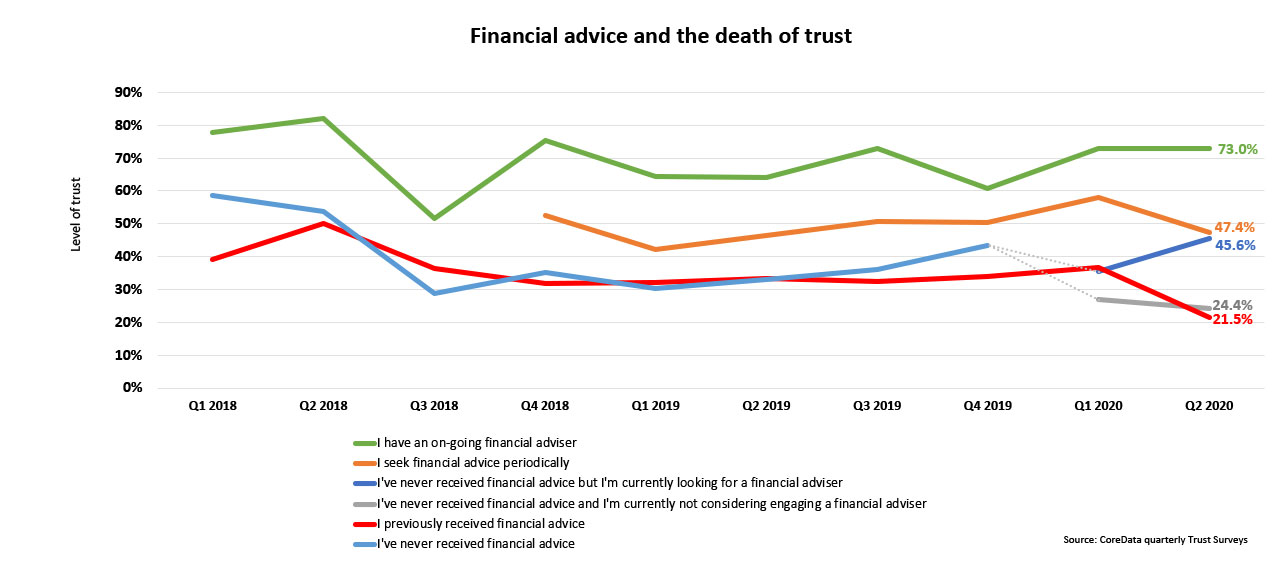

All of that isn’t the point of this article. The point of this article is that when trust, in an experience not a product, goes bad or doesn’t work, it hurts. Have a look at the data below.

This chart comes from the trust research we are doing at CoreData – a quarterly recurring survey on trust In financial services. We are particularly interested in how trust is formed or, more precisely in this case, how it is lost.

When you look at the chart above, in particular the red line which tracks the trust rate of Australians who have previously used a financial adviser and no longer have one, you can it has always been relatively low and recently has fallen quite steeply.

Just keep talking

We have been doing this research regularly for 20 years, give or take; and in survey after survey we have noted that about 30 per cent of Australians who previously had a financial adviser still trusted them. The most common reason that the relationship ended wasn’t lack of trust, it was because the adviser stopped contacting them.

But it appears this may be changing. Over the past four quarters figures have emerged that reveal a level of distrust of advice among a somewhat unexpected cohort. In three of the past four quarters trust among the previously advised has been lower than among people who have never had an advice relationship.

There’s a couple of things to note about the results. In Q3 and Q4 of 2019 we categorised respondents only as having never received financial advice. From Q1 2020 we split this cohort into two: Those who’ve never received financial advice and are not currently looking for an adviser; and those who’ve never received financial advice and are currently looking for an adviser.

The categorisation of respondents as having previously received financial advice remained consistent across the four quarters.

The chicken or the egg

We can’t say from these results alone that all individuals who’ve previously received financial advice and now report a low level of trust in advice necessarily terminated their advice relationship because they lost trust in their adviser. They may have lost trust in their adviser and terminated the relationship, but they also may have terminated the relationship and subsequently lost trust in financial advice.

But clearly there is something going on among this cohort and it may be what behavioural economists call “post-decision rationalisation.”

An individual who has at some point in time sought advice and later decided to stop getting it, may subsequently regret that decision – perhaps they did something they now realise they shouldn’t have, or they’ve seen their financial wellbeing deteriorate after stopping advice.

Rather than admitting to having made a mistake or to regret for breaking off the advice relationship, they may instead now claim they no longer receive advice because they don’t trust financial advisers. They’re saying the fault is with the adviser, rather than with themselves.

A dip or a trend

It’s worth stating that a poor experience for a client, with a consequent loss of trust, is not always the direct result of an adviser’s action (or inaction). For example, poor investment returns – in the wake of the global financial crisis, or due to other calamities – can sour an advice relationship.

It might, however, illustrate why an advice value proposition based on being an investment expert can be at risk of being derailed by forces beyond an adviser’s control.

But here’s the thing: this data doesn’t tell us much, apart from the fact that there is an interesting wobble in the trust rate of Australians who have experienced financial advice.

But we are onto it, we will be digging into this cohort and finding out what’s going on. We will also continue to measure it to see if this is merely a dip in the data, or a trend.