Two men are arrested after holding up a bank and held separately for questioning by the police. How should each of the thieves behave to achieve the optimal outcome? And what can a financial services business learn from a bank robbery?

You may recognise the scenario above as the classic “prisoners’ dilemma”. Each robber is facing a year in jail. But if one testifies against the other, they’ll get six months off their sentence while the other will do a five-year stretch.

If each of the alleged bank robbers pursues a strategy of maximum self-interest – that is, each agrees to testify against the other – their aggregate outcome will be worse than if they co-operate with each other and both refuse to admit guilt. You can read more about the prisoner’s dilemma here if you are not familiar it.

The relationship between a financial services provider and a customer can be thought of in the same terms. If each party to a transaction seeks only to maximise the benefit for themselves, neither party will achieve an optimal outcome.

For our two bank robbers, co-operation is their best path forward, but it can only happen where they trust each other not to put their own interests first. If the first robber thinks the other will roll over, then there’s a strong incentive for the first robber to do the same.

A prisoner’s dilemma

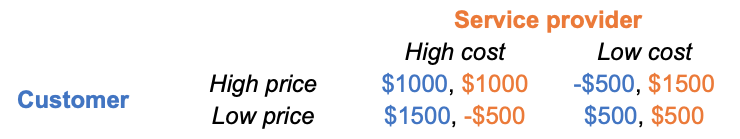

To examine the prisoner’s dilemma in a commercial setting, we assume that a customer has two options: purchase a low-priced service or purchase a high-priced service. Likewise, there are two options for a service provider: provide a high-cost service or provide a low-cost service. The payoff would look like this:

The payoff for a customer is the value of the service less the price of the service; and for a service provider the payoff is what they are paid by the customer, less the cost of providing the service.

Of course, whether a transaction actually occurs between them, and how it occurs, depends on a lot more than a cold analysis of the payoff. Various factors come into play, including information asymmetry, the dynamics of bargaining power, and differences in the level of rationality and intelligence of both parties. The payoff in the real world is a function of all the variables affecting the costs and benefits of a transaction.

The distribution of the payoff is not driven by just one party to a transaction. If a customer wants to pay less, a service provider is incentivised to provide a lower-cost service. They both act in their own interests, and each ends up with a payoff of only $500. But if a customer is willing pay more, a service provider is still incentivised to provide a low-cost service. They end up with a payoff of -$500 and $1500, respectively.

No matter what decision a customer makes, the greatest payoff for the service provider comes from providing a low-cost service. Both parties benefit if they cooperate; if not, the party that cooperates is the one that gets hurt.

Trusting customers co-evolve with co-operative sellers

A service provider must establish trust with a customer, so that the customer does not assume that they are being taken advantage of and will cooperate. If both parties only have to deal with each other once, they are less motivated to build trust by co-operating, and each will tend to squeeze the maximum payoff out of a transaction.

This “game” between a customer and a service provider is spiced up when it occurs in a context where cooperation is incentivised and not co-operating is punished. A properly functioning economy values reputation and seeks to modify or mitigate bad behaviour through laws and regulations. The Royal Commission into Misconduct of Banking, Superannuation and Financial Service Industry exposed numerous instances where regulations had not prevented a lack of co-operation by service providers, which led to poor outcomes for consumers.

The royal commission was meant to identify ways to improve consumer protection. Consumers benefit from such protections because they are then not solely dependent on the benevolence or co-operation of service providers to avoid being disadvantaged.

But another outcome of the royal commission has been to undermine trust in financial services providers. When consumers trust providers less they tend to assume the provider is acting in its own interests and are less inclined to play their part in cooperating to achieve the optimal outcome for both parties.

Play the long game to win back trust

Sensible service providers aim to build a trusting long-term relationship from the beginning, and reinforcing it with repeated experiences.

Research by professor of economics James Andreoni and social scientist John Miller assessed how the duration of a relationship affects people’s tendency to trust. It found that people are more likely to trust a consistent partner: they cooperated 63 per cent of the time compared to only 35 per cent when the counterparty was changed each round.

Perhaps it is not surprising that when each party has an opportunity to prove that they can be trusted to cooperate, through multiple interactions, they each build their reputation for trustworthiness. Even so, it seems this was an approach to dealing with customers that financial services providers lost sight of, and it took the harsh spotlight of the royal commission to refocus attention.