Most of the developed world has enjoyed a population growth dividend lasting for five or six decades in preparation for dealing with an ageing population. But China has enjoyed only 25 years of such a dividend and the problem of dealing with its greying population is already becoming urgent.

China’s well-known one-child policy was terminated and replaced by a two-child policy in 2016 to encourage fertility and alleviate the ageing problem. However, the fertility rate has since remained floating around 1.6 children per woman, well below the replacement rate of 2.1, suggested by the United Nations to have each generation exactly replaced by itself.

The traditional Chinese retirement model has its roots deeply in family: a homegrown pension plan of raising children to support your old age. However, dealing with the “421” legacy of one-child policy – two adults serving four seniors and a child – becomes a common life problem for the 80s generation. The dual effects of fewer kids and more wrinklies put this household aged care model at risk.

The average net income replacement rate (defined as the individual net pension entitlement divided by net pre-retirement earnings) is still below 50 per cent. The amount of pension payment is polarised: a retiree from an urban area collects an average of CNY 4,400 ($920) a month, while a retiree from a rural area only collects CNY 90 ($19) per month.

Rural residents have little in the way of a safety net, and the wealthy believe their assets could have generated better returns with a mature pension system, more developed age-care infrastructure and capital markets.

Retirement built on a three-pillar system

China’s pension system was started in 1991 and gradually evolved to a three-pillar system which has been dominated by the first pillar, consisting of the Public Pension Fund and the National Council for Social Security Fund (SSF). The first pillar accounts for about 70 per cent of the country’s CNY 4.2 trillion of pension assets, while the second pillar – enterprise and occupational annuities – has CNY 1.2 trillion ($240 billion) worth of assets. Private and commercial pensions for individuals represents the third pillar. This is still in its infancy and the scale of its asset is almost negligible. Total pension assets are only about 4.9 per cent of total GDP. This proportion is extremely low compared to Australia, where the assets of superannuation funds are valued at more than 100 per cent of GDP.

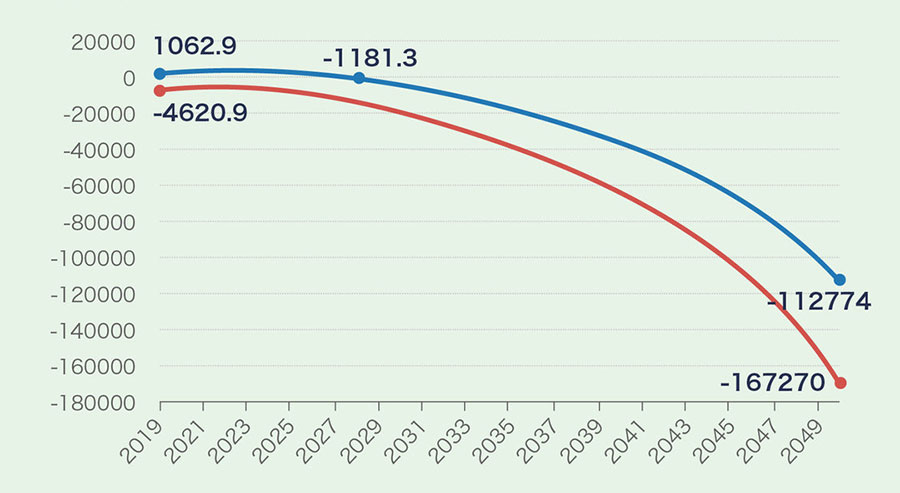

Although the scale of the first pillar has been increasing, without generous central government subsidies China’s pension fund would otherwise be dragged deep into the red. Overreliance on the first pillar and fiscal subsidies is going to aggravate the pension shortfall issue. The pension system supposed to support a population of 1.4 billion is not sustainable without an overhaul. The Chinese Academy of Social Science forecasts that with the current level of financial subsidies the SSF account will be in deficit in 10 years with more retirees drawing capital and fewer people contributing. Furthermore, the investment performance of the SSF has been disappointing – its equity investment return in 2018 was a mere was 2.56 per cent.

The coverage of the second pillar is nowhere near adequate, at only 2 per cent of total employees. What’s more, only 27 per cent of companies paid their full social security contributions, as revealed in a survey conducted by 51Shebao, a social-insurance information provider in China. The development of the second and third pillar is urgent, yet in May 2019, China’s Ministry of Finance officially reduced the enterprise contribution rate from 20 per cent to 16 per cent. The contribution cut has relieved the financial burden on companies, and perhaps brought market vitality to the real economy, but it also shrank the second pillar of the pension system.

A gradual shift towards commercialisation

While the second pillar remains stagnant, or is shrinking, the third pillar is likely to undergo explosive growth. Since 1992 when the American International Assurance Company broke into the Chinese retirement market with its individual salesperson system, China’s retirement business has been gradually moving towards commercialisation. Yet almost 30 years later, the private retirement industry is still a vast blue ocean. Current private commercial offers on the market are homogeneous, savings centric, and not tax-incentivised. It does not cater for various appetites of China’s rising middle class and high-net-worth individuals.

In March 2019, Heng An Standard Life Insurance Company, a subsidiary of a joint venture between UK-based global investment company Standard Life Aberdeen and Chinese state-owned enterprise TEDA International Holding (Group), became the first joint venture that was granted permission to establish a pension insurance company in China. It signals the opening-up of China’s retirement finance industry to western insurers and will have, in turn, a positive impact on the sustainability of China’s capital markets through professional long-term institutional investment.

The Chinese are getting old before they get rich. With a pension crisis simmering, the government is acutely aware of the importance of consolidating and reforming an underdeveloped pension system to take good care of its old. But a comprehensive overhaul cannot be accomplished without affecting various groups with vested interests. How to actually implement the overhaul is another story.