When Commissioner Kenneth Hayne submitted the interim report of the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services industry to the Governor-General and the Parliament in September, it signalled the start of the end for this inquiry.

Those who hoped the report might briefly summarise the hundreds of hours of public hearings and more than 10,000 submissions will have been disappointed; it is a thousand-page catalogue of what happened, what’s wrong and what might be done about it. Those who haven’t read it in its entirety can be excused (although they may find our summary of its findings useful: https://bit.ly/2ORi0yQ).

Even though the report has been read in its entirety only four times across Australia (not an Official CoreData Statistic® but one that is probably true nonetheless), the report garnered significant media attraction with its main findings filling column inches for days. The media attention was intense enough to ensure that Prime Minister Scott Morrison once again apologised for his role in the delay of the inquiry.

Yet while we know what columnists and the Prime Minister thought of the report, what do everyday Australians think of the Royal Commission’s summary? Moreover, we at CoreData wondered how exposure to media coverage informed public opinion and behaviour. As part of a regular series of research conducted throughout the Royal Commission, looking at trust in financial services, we put this concept under the spotlight. The data provides a nuanced perspective on how the reputational fallout of the Royal Commission has been distributed and leaves some hints as to how financial services in Australia might change in the short to medium term.

The insights of the Royal Commission’s interim report have been well circulated by secondary sources but, as expected, very few have even had a peek at the actual report – only one in 20, by our estimation. On the other hand, most have read or watched stories regarding the report as only one in five were completely unaware of its release. Along wealth lines, there’s a general trend towards those of greater affluence having more exposure to the report, save for high-net-worth individuals (those with more than $750,000 of non-residential investable assets), who are interestingly the least exposed. This suggests that the party most interested in the report is the middle-class, or worryingly for financial services institutions, those whom they most rely on for revenue and earnings.

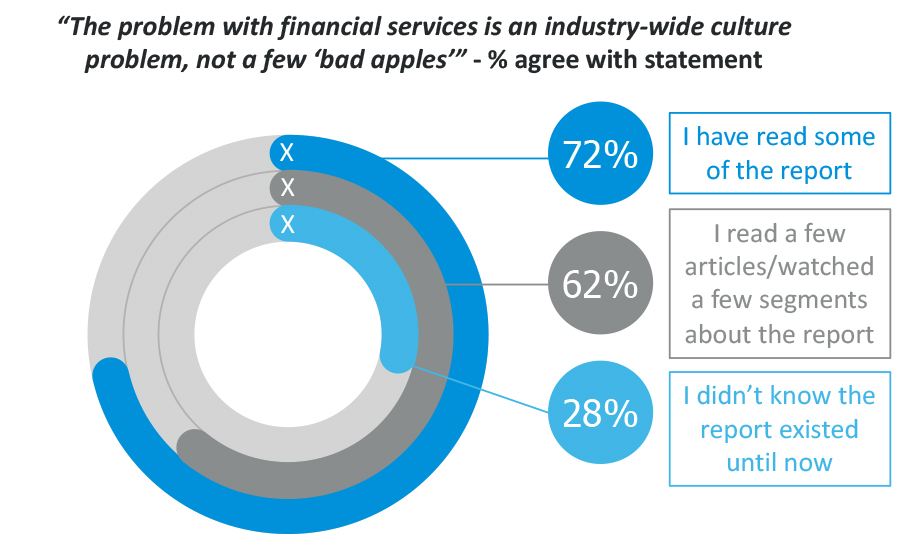

Views on the findings of the Royal Commission hearings vary by one’s exposure to the report. The more they’ve seen, the more the problem with financial services seems to them to be fundamental. It should be noted that superannuation was not covered in the interim report, due to timing constraints, but exposure to the interim report provides a useful proxy for engagement with the hearings more generally, including the hearings into superannuation.

Perhaps more poignant is the belief amongst the “unengaged” cohort that the problem with financial services is mostly “a few bad apples”. It’s surprising that without the benefit of a more detailed account of the hearings, some consumers believe that instances of misconduct, fraud or corruption have been restrained to a few individuals. The interest in the hearings and the outrage generated previously suggested a near-unanimous belief that there’s something fundamentally wrong with financial services in Australia.

While the severity of reputational scars left in the wake of the Royal Commission varies between consumers depending on how closely they follow the hearings, industries bear scars of different sizes too. Superannuation is the most trusted subsection of financial services, now and throughout the Royal Commission, although trust has eroded each quarter for four quarters.

Again, we see those with more exposure to the report express greater dissatisfaction with the financial services fraternity. However, superannuation performs better amongst the cohort highly engaged with the Royal Commission, suggesting that superannuation may have benefitted from the comparison with banking, advice, insurance (life, IP, TPD and trauma) and other segments. Industry super funds, in particular, leave the Royal Commission relatively unscathed: more than half of consumers agree that “industry super funds are more honest than retail super funds”, an opinion that has also grown more stark quarter-on-quarter and is strongest amongst the most engaged.

Not all financial services institutions have been pilloried. ING Direct has seen its reputation considerably improve quarter-on-quarter, in absolute terms and relative to the big four banks. This may be expected, noting that a quick search of all three volumes of the interim report finds the term ‘ING Direct’ mentioned a total of 0 times (a similar search of the terms ‘CBA’ or ‘Commonwealth Bank’ finds them mentioned a total of 1306 times).

Although obviously nowhere near as ubiquitous as CBA, ING Direct’s low cost, technological focus seems to reap some rewards. ING Direct performs better with consumers who have greater engagement with the interim report too, suggesting that ING has benefitted from the poor performance of traditional players and the resultant reputational damage.

These results paint a more nuanced picture of where the Royal Commission has dented reputations. Individuals have markedly different understandings as to the extent of issues afflicting financial services, especially taken on an industry-by-industry basis. Indeed, the results of the survey suggest that exposure to the Royal Commission’s findings correlate with a propensity to consider or change providers.

It is difficult to say how long Australia’s traditional and well-mentioned financial services institutions will be sullied by the Royal Commission, but in the meantime, consumers who have had a little too much of the misconduct uncovered by the hearings will be looking for new providers to demonstrate the capabilities of traditional players, with a fresh take on customer relationship management.