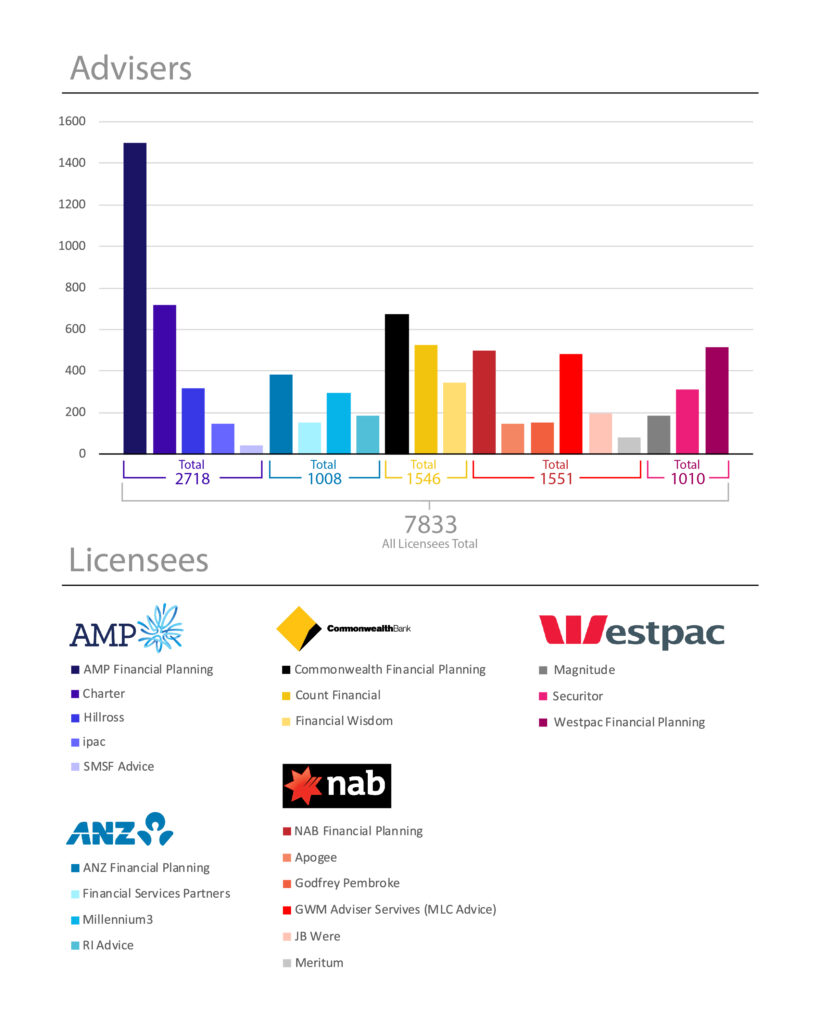

Financial planning licensees controlled by the big four banks and AMP account between for approximately 7800 authorised representatives, or in truth, about half the active market.

With ANZ selling its wealth business to IOOF, NAB recently announcing plans to exit and CBA remaining silent on its intentions, the groundwork has been laid for a radical reshaping of the licensee industry which could affect about half the active market.

The catalyst for this has been The Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry inquiry, which has hastened the move by significant numbers of advisers out of institutionally owned licensees to smaller, non-aligned licensees.

Added to this is the raft of new standards coming down the pipeline from FASEA which will insist on advisers meeting a raft of new educational standards.

As the world changes fundamentally, Koda Capital chair and former NAB wealth group executive, Steve Tucker, says advisers will begin to consider alternative advice structures to ensure their future.

In fact the data on this is clear. Research conducted by Policis in the USA and by CoreData in the UK in 2015 showed that the new regulation changed the structure of the markets fundamentally.

In the UK post-Retail Distribution Review (RDR), adviser numbers shrank by 20 per cent; and in the USA when lending legislation changed, the number of people that simply moved into new structures that were outside the legislation flourished.

So the evidence is clear: distribution markets will either exit or transform.

Tucker says there are issues now facing all licensees that will dictate their ability to accommodate the evolving needs of advisers, and to ensure licensees remain relevant and continue to support advisers effectively.

Five things all financial planning licensees need to be doing

• Deploying capital where it’s going to get the best risk-adjusted return in a vertically integrated business

• Putting the client at the start of the advice process, charging them for the service they get, and eliminating product-related conflicts

• Getting rid of subsidies and having advisers pay fair value for licensee service

• Focusing on strengths and using technology to deliver advice efficiently to targeted markets

• Supporting alternative structures to nurture profitable, scalable advice businesses

Deploying capital

Tucker says financial advice doesn’t stack up like it once did as an attractive use of capital for institutions, and their strategies will adapt to reflect simple economics.

“When you get a return on equity of 21 [per cent] from a mortgage, and your wealth management product lines are now not giving you the economic returns you’re after, why would you have a risky, subsidised advice business that’s built around providing product where the product’s not actually returning as much as your other main products?” he says.

“It makes no sense.”

He says financial institutions are ultimately rational, and as the economics of advice evolve they will consider carefully how they deliver advice and to whom – and whether they should be in the business at all.

Focusing on strengths, using technology

Institutions will play to their strengths, Tucker says, using technology and developments in artificial intelligence to provide “basic, fairly simple and packaged advice to large numbers of Australians”.

“It seems to me that the organisation that’s technology-rich, with a strong capital base and full of large numbers of smart people is better suited to being a product provider than trying to make money out of the advice game,” he says.

“But to the extent they go through the sophisticated, complex advice process, having lots of advisers running around, I don’t think the commercial banks, given the return on equity they can get from other parts of their business, will accept the risk that surrounds that particularly specialist business of advice, and will naturally rationalise how they deliver advice.”

Putting the client at the start

Financial planning is evolving inexorably to a situation where “there is a business and an adviser who is completely unencumbered by any conflict”, Tucker says.

“All they receive is a fee from their client for the advice they provide,” he says.

“That’s where it finishes. Whether it finishes tomorrow or in 10 years’ time, that’s where it finishes. It can go no further than that.

“If you think about where we are today, we’re in that transition from a conflicted system that still relies on subsidy, to this endgame, which is the pure advice profession.”

Charging fair value for licensee services

Tucker says it is “very hard” for institutionally owned licensees to make money from advice, and “they certainly haven’t worked out how to make money out of advice if advice doesn’t distribute their product”.

But today, he says, the competitive advantage has shifted as consumers increasingly demand genuine advice, separate from product considerations. The institutional licensee is caught in the middle, having been built on the premise that aggregation enabled rent to be collected.

“If you flip it into the new world, where aggregation must not attract rent because it creates a bias in the advice outcome, you say well, you need a new model,” Tucker says.

“But because there has been that rent from aggregation, the advisers have never paid what they should pay. The economics has been distorted. If you think the endgame is nearer rather than further away, and the economics has unravelled, and the subsidies can’t exist, then the licensee structure which as existed out of the rent can’t exist. One follows the other.”

Supporting new structures

Tucker maintains a partnership is the ultimate structure for supporting independent, unconflicted and professional advice. It is the endgame of the evolution of the advice business.

“There’s no further to go,” he says. “It can’t go any further.

Tucker says Koda has operated as a partnership for the past five years, but it’s a throwback to a structure that existed in advice 30 years ago and which has long existed in other professions. It’s a structure where the business owners and the licenceholder are one and the same, which can be economically viable and deliver unconflicted advice.

“There’s only a licensee in that structure because the law says there has to be a licensee,” Tucker says.

“The partners own the business and the business holds the licence.

“But the business of the licensee isn’t trying to aggregate and create some rent from that aggregation; the business of the licensee is simply we have a licence because we need that to provide advice through the partnership.”