Nearly half of consumers who currently have income protection insurance believe they would be covered in the event of job loss, new research from CoreData has found.

The research, based on a survey of more than 500 Australians conducted in April, sheds light on the risks facing life insurance companies and financial planners selling disability income insurance (DII) policies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It also presents a challenge for life companies in adhering to the looming Design and Distribution Obligations (DDO), due to take effect on October 5 next year.

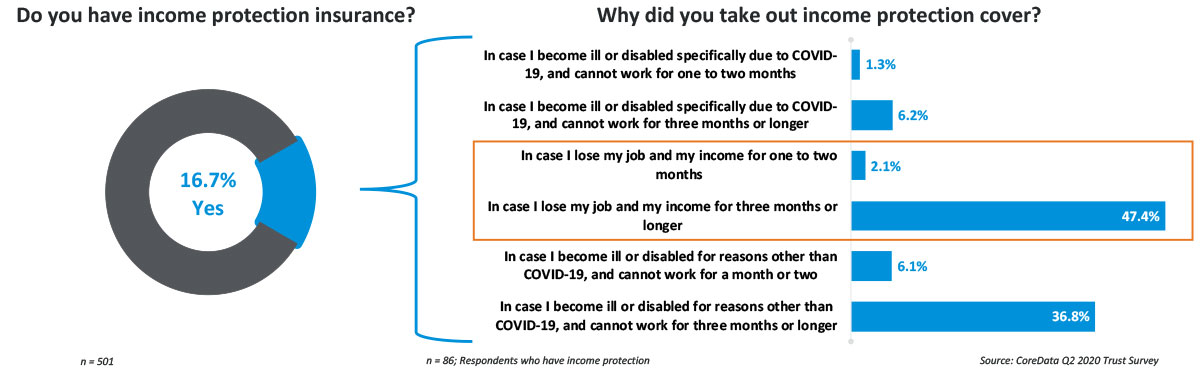

The research revealed that of the 16.7 per cent of respondents who had income protection insurance, nearly half (49.5 per cent) took out the cover in case they lost their job and income.

Among the general population, this misperception that a DII policy would pay out in the event of job loss or unemployment is held by nearly seven in 10 respondents (68.3 per cent).

With DDO coming into effect next year, and the cessation of agreed value income protection contracts this year, it is critical that consumers are not being mis-sold an insurance policy they don’t actually need, or wouldn’t have taken out if they’d understood what it covered.

During a CoreData virtual roundtable with life insurance executives in May, some suggested it might be worth changing the name of the cover to make it more specific to illness and injury.

One executive said the company had opted to stop selling IP during COVID-19 after a spike in sales, due to concerns that people were purchasing it without really understanding it. Indeed, the research found a small proportion of people (7.5 per cent) had taken up the cover in case they became ill or disabled due to COVID-19.

However another executive noted that despite some confusion among consumers about whether IP contracts covered them if they became unemployed, this confusion did not translate into complaints to life companies, suggesting that most of those that have IP cover – particularly through advisers – understand it.

Insurance illiteracy poses challenges for insurers under DDO

The draft Regulatory Guide on DDO and ASIC’s Consultation Paper 325 released on 19 December 2019 set out ASIC’s proposal for guidance on DDO and its administration. The obligations were originally due to commence in April, but were deferred six months due to the impact of COVID-19 on the Australian economy.

ASIC intends the DDO to ‘drive better business and consumer outcomes’, by ensuring product issuers and distributors design products that meet genuine consumer needs. The obligations are also, in part, an answer to the Hayne Royal Commission findings about mis-selling of financial products. Under the obligations, ASIC requires product manufacturers to not only identify the target market for their products, but also the ‘negative target market’. In other words, who is the product not suitable for?

The target market determination (TMD) must detail the nature and complexity of the product and what it provides the customer, as well as the characteristics, objectives and needs of the retail consumers it’s targeting.

This customer-centric approach to product design will require financial product manufacturers to have sound understanding of how advisers and financial planning practices are assessing customer needs and matching products to their circumstances. From the adviser perspective, a TMD for a financial product should be considered in the provision of advice and as part of meeting their best interests duty.

ASIC proposes to give guidance that consumer understanding alone is an insufficient basis for determining the target market, because “there is broad recognition that reliance on the concept of the ‘informed consumer’ is not resulting in good consumer outcomes”. So the reasoning goes, just because a person understands a product, it doesn’t mean it’s consistent with their objectives, financial situation or needs.

However, there is an expectation from ASIC that product distributors do not take advantage of behavioural biases or factors that can impede consumer outcomes. They must also consider ‘consumer vulnerabilities’ and how these vulnerabilities may increase the risk that products sold to consumers fail to meet their needs, leading to poor outcomes. These vulnerabilities may include a person’s personal circumstances, as well as the influence or impact of features in a product’s ‘choice architecture’.

“It’s likely that the pandemic and its impact on unemployment

in Australia has called into question the viability

of continuing to offer such products in the future.”

A study of consumer vulnerabilities across key European markets in 2016 found vulnerability was highest when consumers face complex advertising, don’t compare deals, or have problems comparing deals because of market-related factors or personal factors. There are fewer markets more complicated than financial services.

Given this, it could be argued that insurance illiteracy is in fact a consumer vulnerability, in that lack of understanding of the situations in which an insurance product you’ve purchased covers you is surely a foundation for a poor consumer outcome.

There are insurances that pay out if you lose your job, but DII isn’t one of them. These unemployment cover benefits are often wrapped up as part of a loan protection plan and intended to pay out, after a designated wait period, if you become ‘involuntarily unemployed’ due to redundancy or retrenchment from full time-time employment.

It’s likely that the pandemic and its impact on unemployment in Australia has called into question the viability of continuing to offer such products in the future.

The key concern for life companies and financial advisers, however, should be whether any of those who rushed to take out DII policies amidst the coronavirus crisis did so due to the stark focus the pandemic brought on job insecurity. And in doing so, assumed they were protecting themselves from the risk of future unemployment.