Australia’s ageing population is one of the biggest challenges facing the country in the next 20 years.

In its second background paper published in May, the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety acknowledges that by 2058 the number of Australians aged 85 years or older will increase to more than 1.5 million people, or 3.7 per cent of the population.

Currently, there are 4.2 working-age Australians for every Australian aged 65 years or over. By 2058, it will have decreased to 3.1.

The background paper, Medium and Long-term Pressures on the System: The Changing Demographics and Dynamics of Aged Care, highlights the need for “significant adjustments to the Australian economy and systems that support older people” as a result of demographic, social and economic pressures. However, it cautions that the demographic changes anticipated are unlikely to be any greater than those that have occurred over the last 40 years.

“By 2058, there will only be 14.6 people of traditional working age (15–64) for every person aged 85 or older. This rapid decline has implications not only for the financing of aged care but also for the aged care workforce, which will face relatively fewer workers to draw on to meet the growing demand for services,” the paper says.

Show me the money

The big question that remains is who will fund these significant adjustments.

In the lead up to the May Federal Election, both the government and opposition have been curiously silent on long-term reforms to the sector.

While there is certainly a need to improve the quality of care and outcomes for elderly Australians, this comes at a cost, and with most of the large aged care providers posting year-on-year losses in recent financial years, it’s not entirely clear how these changes will be funded.

Low occupancy rates, combined with increasing staff costs, have contributed to falling profits in the residential aged care sector. Profits are expected to continue their decline as earnings fall and costs continue to rise.

Recently, Aged and Community Services Australia called on the elected government to extend the 9.5 per cent funding injection into residential care and boost level 3 and 4 Home Care Packages by 40,000 in 2019-20, along with other measures that it said could be implemented before the Royal Commission finishes its inquiry.

Whether government action is taken remains to be seen, but one thing is for sure; the cost of care will burn a larger hole in consumers’ hip pocket in the future.

The paper clearly signals the increasing wealth of those now retiring and currently in the workforce, and the greater potential capacity for them to pay for their own care. While acknowledging there will be a significant group of older people with low incomes and little wealth, the paper notes people now reaching the eligibility age for the age pension are ‘significantly wealthier’ in real terms than their mothers and fathers were at the same time of life.

A shift in the structure of supply

The background paper focuses on the structural changes the industry is undergoing as a result of evolving consumer preferences and the prevalence of dementia among older Australians.

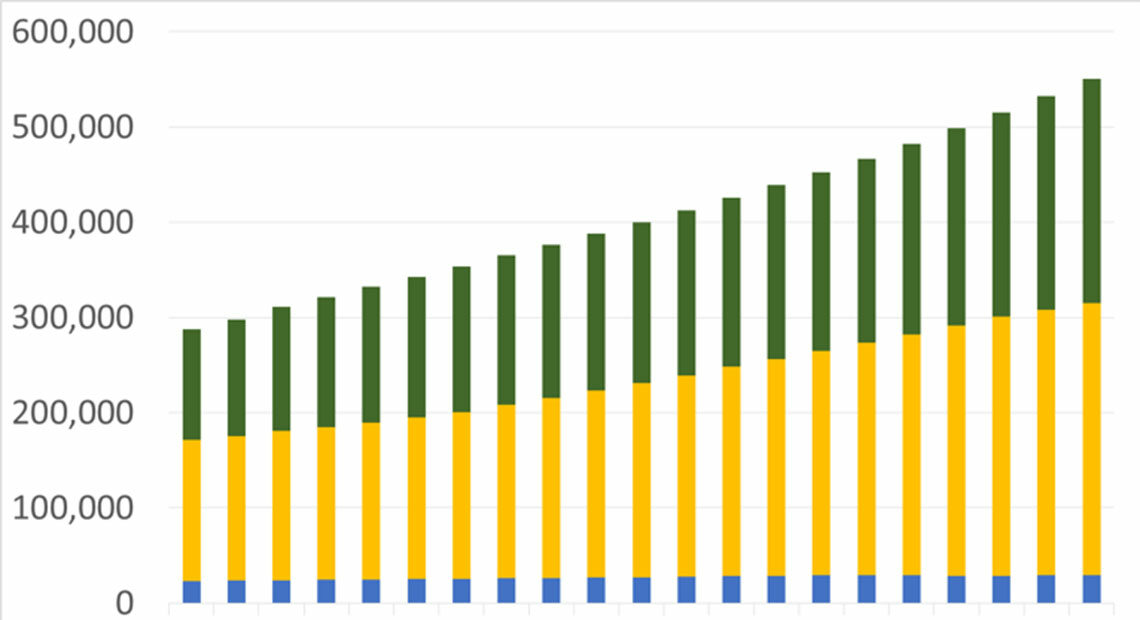

It says that by 2030, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare estimates about 550,000 Australians will have dementia, with 42.8 per cent of those aged 85 years or older.

Home care is becoming increasingly common and desirable, as people seek ways to live independently for as long as possible, in the comfort of their own home, and remain connected to their local community as they age.

Yet longer life expectancy means we’re living to an age where chronic conditions are more common, requiring greater focus on delivering complex care in the home.

Growing demand

The paper highlights a growing need for two types of care: in-home or community care, including retirement villages or ‘life care’ communities that integrate home and care; and high-level residential care for those with complex health needs or dementia.

Demand for the latter will increase, the paper notes, with the growing incidence of chronic conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, severe arthritis and serious visual and hearing impairments that restrict people’s ability to live independently.

“People will be able to receive the care that they need in their home for a longer period of time and to a greater intensity,” the paper says.

“Movement into residential aged care will be delayed and only occur at higher levels of frailty than currently.”

Innovation is required in both service provision and delivery, and the gauntlet has been thrown down to the sector to be flexible in responding to the changing needs of elderly people over time.

But innovation can be costly, and a thriving sector is more readily able to adapt and respond to changing demographics and community expectations than one that is unprofitable and struggling to keep the doors open.

The inquiry must pay heed not only to the scale of change required to ensure quality outcomes for aged care consumers, but to how these changes can be appropriately managed and funded to support ongoing competition and sustainability in the sector.