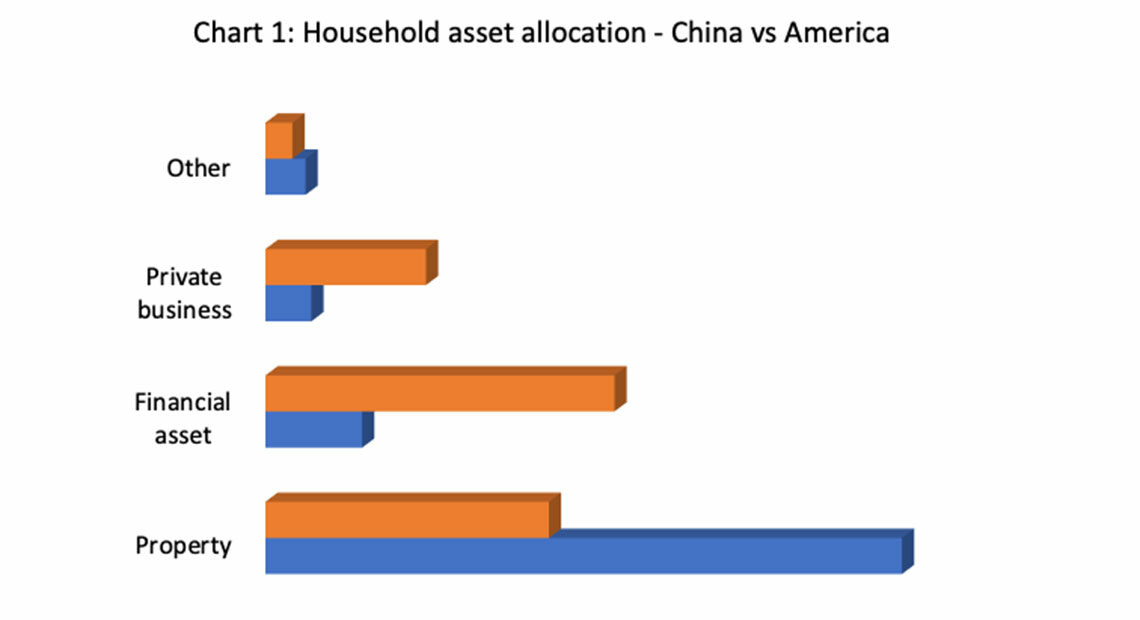

The value of residential property as a proportion of the total value of household assets in China is more than double the level in the US. At 77.7 per cent of total assets, compared to 34.6 per cent in the US, the figure may sound striking but it is quite understandable in a developing country such as China.

A strong emotional attachment to housing is deeply rooted in the massive Chinese population. Many Chinese believed they would enjoy jobs for life, but the State-owned enterprise reforms of the early 1990s shattered that dream. The anxiety of not being able to have a secure life has been haunting them ever since.

Current social policies and conventions discriminate against those who do not own their own homes, the legal system favours property owners over tenants, and underdeveloped capital markets provide limited financial product choices. Owning a property became the last hope for many Chinese to live with dignity.

Such a reliance on property sustained strong demand, with surging house prices in turn encouraging speculative investment. But in 2010, regulation started to tighten, including increasing the deposit needed to buy a home, suppressing the housing market.

Consequently, prices immediately dropped, with a short-lived decline in transaction volumes, but all the increased regulation failed to alter the fundamental mismatch between supply and demand, or to dampen enthusiasm from property speculators.

Inflated house prices, yet optimistic anticipation

Today, just 30 minutes’ drive away from downtown Shanghai, a 98-square-meter three-bedroom apartment with bland suburban-sprawl views is on the market for RMB5.7 million ($1.2 million), whereas the average income in Shanghai is about $16,000.

These figures would suggest a big property bubble is forming. But the People’s Bank of China First Quarter Urban Household Survey 2019 shows that only about 10 per cent of 20,000 respondents expect the housing market to be bearish in the next quarter. In general, the Chinese population holds strong confidence in the government’s ability to prevent the housing market from collapsing. However, the overinflated property market crowds out development of other asset classes. Higher housing values are usually accompanied by higher liquidity risk, which discourages households to invest in risky assets. In China, the negative effect of housing values on financial market participation gets less intensive as household wealth increases, according to research published by Emerging Markets Finance and Trade.

Sub-healthy financial status of Chinese households

The price of being financially and psychologically secured by the ownership of real estate is the opportunity cost of investing in other long-term assets. Out of the 11.8 per cent of Chinese household assets held in financial assets, bank deposits account for 43 per cent, followed by insurance and financial products; and risky assets such as equities and funds account for 11 per cent of total financial assets.

The imbalanced asset allocation, plus limited investment choices, leave the financial state of Chinese households sub-healthy. However, it should be acknowledged that in fact since 2013, the range of financial products available to Chinese investors has expanded, which signifies a trend of financial product diversification.

Younger home buyers, a greater deal of pressure

According to Shell Research Institute, a Chinese research centre focusing on real estate, the average age of a Chinese primary home buyer was 29.5 in 2018, far younger than their counterparts in other countries.

How could they possibly afford such outrageously expensive homes given the limited wage level?

Buying a home requires a lot of sacrifice by Chinese families. It can cost 20 years’ of parents’ savings – and sometime the parents’ entire savings – plus the home buyer’s own savings and a proportion of their future income.

From 2013 to 2017, total household debt increased by 9 per cent a year, mainly driven by housing mortgage debt. Meanwhile, the household deposit-to-disposable-income ratio dropped to 12.7 per cent in 2017 from 25.4 per cent in 2010. Homeowners feel secure being millionaires by the book value of their properties, even though they are overconsuming their future. On the other hand, people who cannot afford properties are anxious about missing the “wave”.

After all, without the expectation of capital growth, and in the absence of appropriate exit avenues, property is merely a consumable in the guise of investment.

When a bird’s nest is overturned, no egg remains intact

China has long been one of the countries with the highest saving rate. Now the age of debt has already begun, and its scale keeps expanding. The government is facing a nasty situation, where its sacred political goal of GDP growth between 6 per cent and 6.5 per cent in 2019 will be not achieved if it keeps curbing homebuyers and credit expansion.

However with another boost from a loose lending policy, a housing market that is on the brink of collapse may boom again. No matter how much Chinese believe in the power of the government, every boom leads us one step closer to a bust, and if household debt becomes unsustainable it will be more than just an issue of soft landing or hard landing.

No one can accurately predict where the Chinese property market is going in the short term. In the long term, there is not enough wood to burn.