In the short term, the exit of major financial institutions from the advice industry will cause disruption to advisers, and potentially to clients. But in the long run, it will be seen as a step towards professionalising an industry, and in establishing financial advice as a professional service.

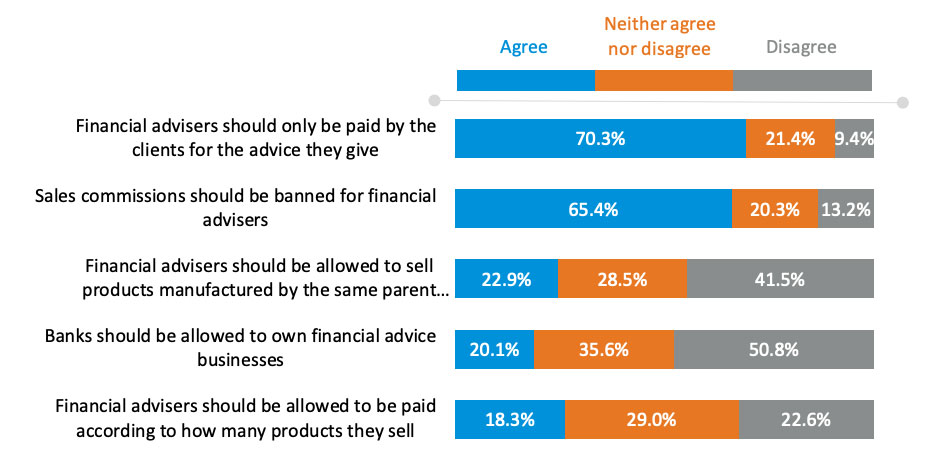

Earlier this year, CoreData asked consumers about their expectations of financial services companies and financial advisers specifically. Their response was clear: more than 70 per cent say financial advisers should only be paid by the clients for the advice they give. Only 23 per cent agree it is OK for financial advisers to sell products manufactured by the same parent entity that owns the advice business; only 20 per cent agree it’s OK for banks to own advice businesses at all; and only 18 per cent or so think advisers should be paid on the basis of how much product they sell. The changes occurring in the advice industry now reflect these expectations.

It was suggested in media reports this week that a root cause of the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry was the banks’ failure to adequately monitor what they sold, and to whom. That’s true as far as it goes, and also if we look back in time. The banks knew what they were selling, because sales targets were common across the organisations. And they knew who they were selling it to, because referrals and leads were also closely monitored. What they failed to adequately monitor was how products were sold. In other words, when product was the focus, “advice” frequently became a mechanism to soften up the consumer for a sale.

In more recent years the banks sought to address this issue, but in some instances it was too late. Poor compliance around the provision of advice had already done the damage, which led to the remediation programs we see today. Commonwealth Bank and National Australia Bank have responded by preparing to divest advice businesses (notwithstanding CBA’s recent announcement of a delay in proceedings); and this week Westpac confirmed its intention to exit the advice industry, with its advisers offered the opportunity to migrate to the Melbourne-based Viridian Advisory. Viridian will take on as many as 175 employed BT advisers and support staff and offer a home to advisers authorised through the Westpac-owned Securitor and Magnitude licensees.

Viridian’s move to increase its presence in the advice space represents a vote of confidence in advice as a viable, profitable and valuable professional service.

Viridian’s chief executive officer and co-founder, Glenn Calder, says the firm’s shared background with Westpac will make a transition as smooth as possible for advisers and clients. Many of the Viridian executives and staff came from the Westpac/BT advice group, including Calder himself and Viridian’s highly regarded chief investment officer, Piers Bolger.

The exit of big institutions from advice sets the scene for the provision of advice as a professional service to be clearly and structurally separated from product. The lines between product and advice will become that little bit less blurred. Advisers will be empowered to a greater extent to articulate, value and sell their services as professionals, with the potential conflicts that arise from product sales significantly diminished.

It is not a sign that the advice industry is diminishing in value or in significance or is somehow in terminal decline. Advice remains a service highly valued by those who experience it. Close to 70 per cent of individuals who pay for advice agree or strongly agree they receive good value for the fees they pay. Less than 9 per cent disagree or strongly disagree.

These moves are, to a certain extent, an evolutionary stage of financial advice from industry to profession. There are few other recognised professions in the world that are dominated by major institutions. They may be dominated by large organisations, but they are professional services firms.

Regulatory changes already made, among them the Future of Financial Advice(FoFA) laws, had started to drive changes in the structure of the wealth management industry, and in how participants in the wealth management chain related to each other and to advisers’ clients.

The phased introduction of higher education, professional and ethical standards for financial advisers, overseen by the Financial Adviser Standards and Ethics Authority (FASEA), will drive that change further as advisers are required to take on greater individual professional responsibility and accountability. These responsibilities further reinforce the concept that the adviser is there to act in the best interests of the client and the client alone (a concept introduced under FoFA); the viability of advice businesses supported by product sales is further diminished.

And the recommendations of the royal commission make it clear that actions or behaviour not directed at serving the best interests of the consumer won’t be tolerated. Commissioner Kenneth Hayne wrote at page two of his final report that in the financial services industry there had been “a marked imbalance of power and knowledge between those providing the product or service and those acquiring it”. In case it’s not yet clear, it is perhaps worth stating that it’s the role of a professional adviser to counter that “marked imbalance” on behalf of their client, not to exploit it.

Hayne wrote: “Consumers often dealt with a financial services entity through an intermediary. The client might assume that the person standing between the client and the entity that would provide a financial service or product acted for the client and in the client’s interests. But, in many cases, the intermediary is paid by, and may act in the interests of, the provider of the service or product. Or, if the intermediary does not act for the provider, the intermediary may act only in the interests of the intermediary. The interests of client, intermediary and provider of a product or service are not only different, they are opposed.”

Much of the regulation of financial advice, both in place and in the pipeline, was developed to address issues that arose from a product-centric view of the world. Indeed, much of the legislation and regulation that governs advice – a service – has been focused on addressing what must be done for and disclosed to clients when selling a financial product.

The retreat from financial advice of the nation’s largest financial institutions is not evidence that financial advice is dead as a business. But it is further evidence that financial advice propped up by product sales is dead as a business. The provision of financial advice as a professional service – strategic, separate from product, focused on the client – remains alive and well.