In presentations by CoreData to financial planners, licensees and product manufacturers about the future of advice and distribution, there’s a slide we’ve titled “Ken Hayne and the Destruction of Trust”.

“Great name for a band,” the line goes, “but not so good for the financial services industry.”

If Ken Hayne and the Destruction of Trust had just released a new album – let’s call it “76 Things I Hate About You” – it might initially be reviewed as slightly underwhelming and a bit disappointing, given their earlier work (“Interim Report”, an EP released in September last year). Their A&R man might say: “I don’t hear a single!” But the future is wide open.*

Like other classic albums before it, it’s a sleeper and reveals its depths more fully on repeated spins. It’s more a slow burn than a damp squib.

In the absence of a few big-bang recommendations, it’s necessary to take a step back to consider the bigger picture, and the broader environment that commissioner Hayne has sought to address. If the report had contained a number of hand grenades the response might be clearer, or more obvious. For example, a recommendation to dismantle vertical integration would have clear, obvious and startling implications. If it recommended wholesale legislative reform, it would at least have created a clear focal point for commentary and analysis.

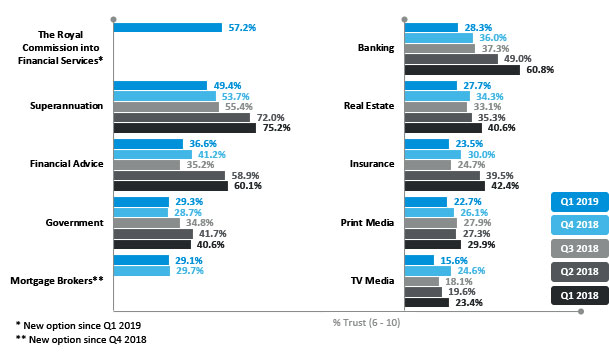

The destruction of trust

But it doesn’t do that. It recommends that existing law be better applied; that conflicts be managed or eliminated but without dismantling existing structures; that regulators police misconduct better and punish offenders more appropriately; and that leadership, culture and governance be improved. All well and good, but no big bang.

That is less conducive to strong headlines, takes longer to analyse, and means licensees and advisers will be learning in the weeks and months ahead how the pieces fit together, and how they relate to and perhaps modify the application of existing law.

However, all of the recommendations in the final report can be viewed through a prism of seeking to make the wealth management value chain flatter, simpler and more aligned to delivering services in the best interests of the client. This is the message that comes through clearly in CoreData’s Future of Advice and Future of Distribution work, and the royal commission recommendations, if accepted and enacted by government, will only accelerate that trend. What the commission demands of advisers and licensees – of all financial services providers, for that matter – is summed up in six simple principles:

1. Obey the law

2. Do not mislead or deceive

3. Act fairly

4. Provide services that are fit for purpose

5. Deliver services with reasonable care and skill

6. When acting for another, act in the best interests of that other.

Mercifully, minimal additional or amended legislation is proposed to encourage licensees and advisers to meet those aims. Rather, the inquiry lobs the ball into the regulators’ court and demands the start hitting a few winners by enforcing existing laws better and applying sanctions that actually spur a change in behaviour.

Some insight into how ASIC, in particular, has already changed its approach comes from its recent action constraining Commonwealth Financial Planning (CFPL) from charging fees for ongoing advice and preventing it from entering into new ongoing service arrangements unless and until it improves its response to an earlier enforceable undertaking. Advisers and licensees alike should expect more actions like this. Hayne has reminded regulators of their responsibilities, emboldened them to take tougher action, and put the industry on notice of what to expect.

Hayne’s report contains 76 recommendations all-up, designed to address the root causes of misconduct (namely, greed and dishonesty) identified over the course of his inquiry, and to modify behaviour that has failed to meet community expectations.

For advisers and licensees there are a number of significant recommendations, including: the creation of a new independent disciplinary body; the removal of the best interests duty “safe harbour” provision; the abolition of grandfathered conflicted remuneration; the abolition of life insurance commissions; changes to ongoing fee arrangements (including, in effect, reintroducing an annual opt-in); and disclosure of when an adviser doesn’t meet the definition of independent, impartial or unbiased under section 923A of the Corporations Act.

A number of those actions are proposed. The safe harbour provisions will only go if, upon a future review, other measures are found to have independently improved the quality of advice. Life insurance commission will only be removed if an ASIC review, also down the track, supports that idea.

The final report’s Recommendation 2.10 relates to a proposed single, central disciplinary system for advisers. It recommends the system should be compulsory for all financial advisers who provide personal financial advice to retail clients; that licensees should be compelled to report to the body any “serious compliance concerns” they have with advisers; and that clients “and other stakeholders” should be allowed to report to the body information about adviser conduct.

It’s not hard to see where this recommendation comes from. Repeatedly during public hearings last year, stakeholders in the financial planning industry were shown to have failed to identify, report and act upon concerns either reported to them or identified for themselves.

It’s the lack of appropriate sanctions – both in force and timeliness – for misconduct across all sectors of financial services, not just financial advice, that informs a significant number of the inquiry’s final recommendations. Financial advice can’t escape that.

Stopping the industry’s so-called “bad apples” licensee-hopping (or what Hayne describes as “rolling bad apples” – not quite as catchy a name for a band) also gets some attention. Hayne says that licensees are not doing enough to “communicate between themselves about the backgrounds of prospective employees”. It’s to be hoped that “employees” actually includes authorised representatives, because targeting only employed advisers makes little sense in the context of recommendations designed to address an entire sector.

Second, Hayne says, licensees are not sharing enough information with ASIC about advisers. He recommends the reference-checking and information-sharing protocol developed by the Australian Bankers Association become mandatory for licensees; and that ASIC’s intelligence-gathering and trend-spotting prowess be improved through a formalised form of reporting to it by licensees of compliance concerns which might not be severe enough to trigger the reporting requirement under s912D of the Corporations Act.

So taken as a piece of work – an album, if you will, rather than a few hit singles – the Hayne report describes a future for financial advisers and licensees that is not massively different from the current environment, but with sharper misconduct reporting requirements, a clearer focus on clients’ best interests, an elevated likelihood of meaningful (and painful) sanctions for breaches of the law, and an environment where professional conduct and behaviour is not optional – subject to voluntary codes and motherhood statements – but demanded by law.

Changes for financial planning seem relatively benign this time around partly because the royal commission’s terms of reference required it to take into account any law reforms already announced by the Commonwealth Government, which includes new education, professional and ethical standards.

Financial planning has had more than its fair share of regulatory upheaval over the past decade. Hayne’s approach of simplifying the law where possible and enforcing it more effectively, should be welcomed.

* With apologies to Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers