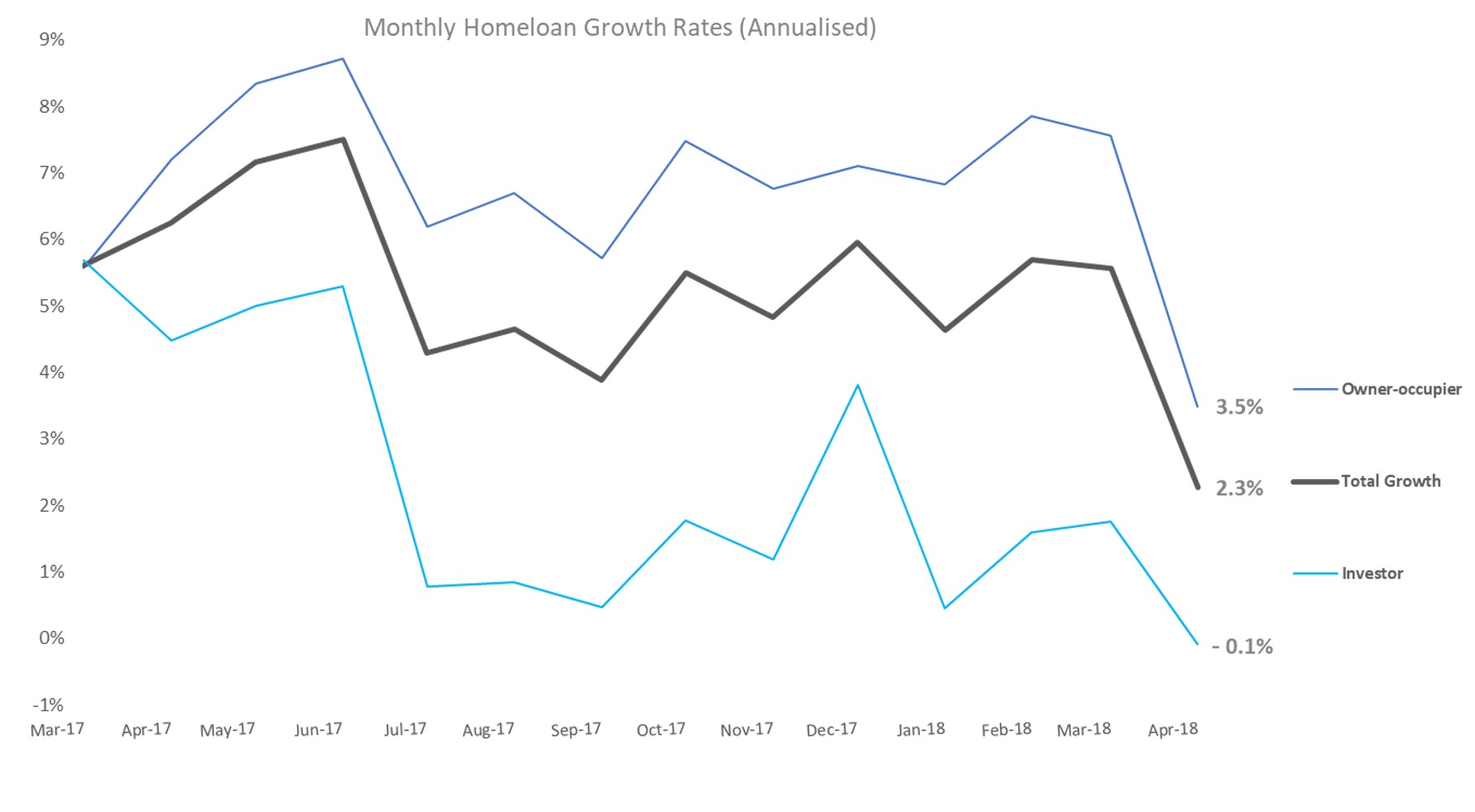

The release of the latest Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) monthly banking statistics show annualised monthly growth in home loans has dropped to 2.25 per cent – the lowest growth figure recorded since September 2015 – and growth in investor lending has contracted, to -0.1 per cent.

At first glance the figures seem puzzling, because in April APRA said that from July 1 this year it would drop the cap on how much banks can grow investor loan books. But at the same time the regulator tightened up on a number of other lending measures and restrictions, and the move comes after two weeks of public hearings at the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry, which focused on consumer lending.

In a letter dated April 29, 2018, APRA said the benchmark on investor loan growth will “no longer apply from 1 July 2018 where an ADI has been operating below it for at least the past 6 months, and the ADI’s Board has provided the required assurance to APRA on both lending policies and practices”.

However, APRA warned that “a return to more rapid rates of investor loan growth at an aggregate level would nevertheless raise systemic concerns”.

“Such an environment could lead APRA to consider, for example, the need to apply the counter-cyclical capital buffer or some other industry-wide measure,” it said. The same letter said a benchmark on interest-only lending would remain in place.

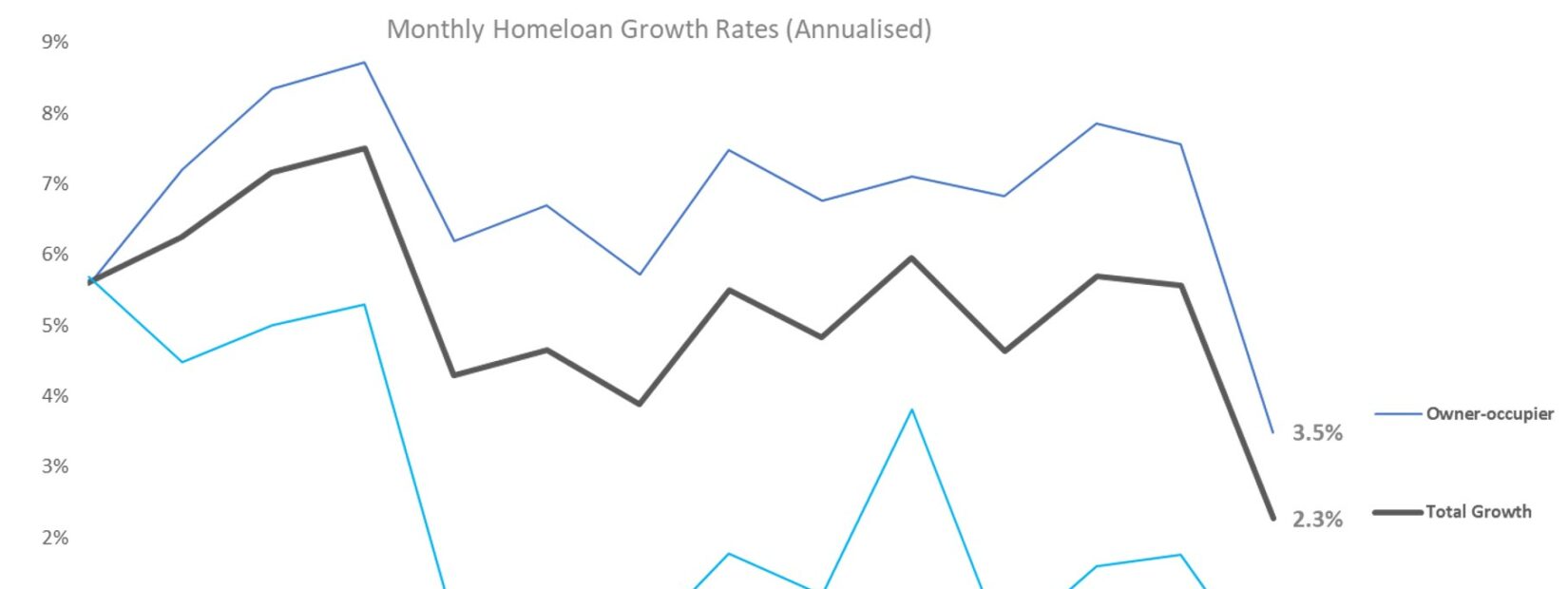

Source: CoreData, APRA Monthly Banking Statistics

The latest monthly lending figures look like APRA may have gone too far, although apportioning blame to a single factor is always fraught.

The picture is complicated by the royal commission’s public hearings into consumer lending which ran from March 13 to 23 this year.

As a result of a focus by that inquiry on how stringently brokers and lenders alike have been vetting and verifying loan applications, brokers are being asked to gather more evidence from clients on living expenses and debts, leading to an increase in both their costs and loan-approval times.

The lending market had been tracking at annualised monthly growth rate of just over 5.5 per cent to the end of March, during the royal commission’s public hearings, but took a dive in April.

Lenders are already operating close to APRA’s guidelines (see table, below), with apparently limited room to move. Critical to this assessment is the definition of “comfortably” in relation to how lenders’ current positions compare APRA’s guidelines.

Is a serviceability buffer 0.25 percentage points greater than APRA’s required 2 per cent buffer really “comfortably” greater? And is a floor interest rate 0.25 percentage points greater than APRA’s required 7 per cent really “comfortably” greater?

And now APRA is also demanding that lenders focus on improving, where necessary, the collection of information on borrowers’ actual expenses, to reduce reliance on benchmark estimates.

The regulator’s letter to lenders says the use of benchmarks should be “closely monitored, and applied in a low proportion of lending, consistent with the typically low calibration of such estimates” – that is, it wants lenders to reduce lending based on living expenses calculated using the Household Expenditure Method (HEM).

It wants lenders to develop limits on the proportion of new lending at very high debt to income levels (where debt is greater than six times a borrower’s income), and to set limits on maximum debt to income levels for individual borrowers.

It is difficult to see how banks can continue to comfortably grow investor loan books with APRA restrictions remaining in place.

Further scrutiny of living expenses and lenders interpretation of what “comfortably” means is likely to temper any benefits from APRA lifting the 10 per cent investor growth rule and may further depress owner occupied lending.

This continued subdued growth is likely to also lead to increased price competition on both investor and owner-occupied lending, reducing banks margins and putting further pressure on banks to reduce their costs.